There are a lot of devices out there that include heart rate monitors, from stationary devices like treadmills and ellipticals to fitness bands to bicycle computers. People often ask whether the calorie measurements are any good, so I thought it would be useful to talk about how they determine calories and what you can expect in terms of accuracy.

Metabolic testing

The gold standard for measuring calorie burn is through metabolic testing. You exercise on a treadmill or exercise bike wearing a mask that collects all of the air that exhale. By analyzing your exhalations, a very accurate measurement of how many calories you are burning can be determined.

The test is usually one that increases in intensity, and along the way, your heart rate is recorded. One of the results that you get out of the test (there is a ton of data collected, including your V02Max, a measure of your overall fitness) is a table that records your calorie burn rate at various heart rates.

|

Heart Rate |

Calories per minute |

| 118 | 0.117 |

| 135 | 0.173 |

| 144 | 0.199 |

In a real test, there would be a lot more data than this.

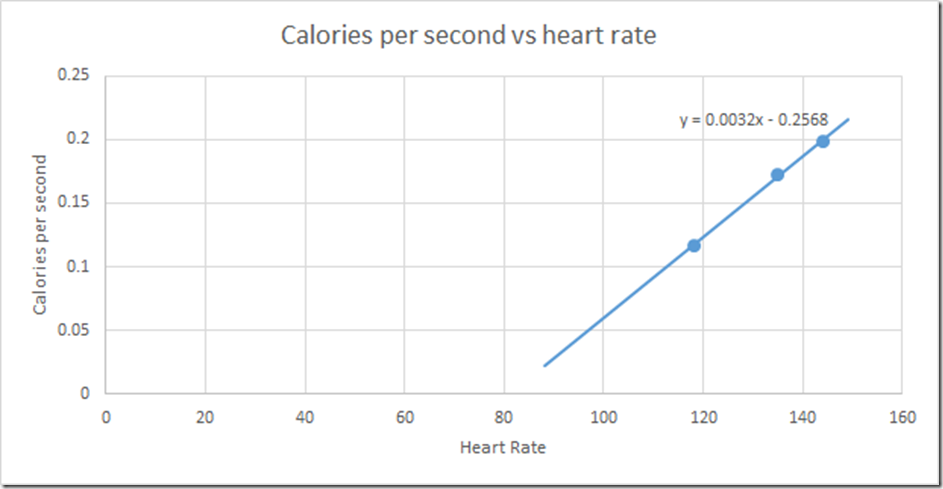

I can put the data in a graph, and do a little math on it:

The line through data point is a calculated curve it through the points. In this case, it’s a straight line, but in the real world, a curve will probably be a better choice.

We also get a formula out of the calculation:

Calories/Second = Heart rate * 0.0032 – 0.2568

If I know the heart rate on a second-by-second basis, I can use the formula to estimate the calorie burn for that second. If we were doing an experiment where we wanted to measure the calorie burn of a group of subjects, we would do this for each of them, and then we could just ask them to wear a heart rate monitor during the experiment, and use their personal equations to calculate calorie burn. This is a very common approach for exercise studies.

Note that we are predicting the total amount of calories burnt by the person at a given heart rate, not the excess number of calories due to exercise.

Heart rate monitors

Enter the general-purpose heart rate monitor. They would like to provide you a measurement of your calorie burn, but they have a serious problem – they do not have results from a lab test to use.

What to do, what to do?

Well, what they do is they recruit a bunch of volunteers, and they put each of them through metabolic testing, average all the data together, and come up with a single equation.

This does not work well. Not well at all. There is a ton of variability among people; some have large hearts, some have small hearts, etc. This means that the prediction is not very good.

So, they start collecting more data about each of the participants – what is their age, their height, their weight, their sex, their exercise level, the breed of their dog – and they feed this into some statistical software, and they end up with what is known as a model, This is just a very fancy equation where you plug in the demographic information (age/sex/etc.) and the current heart rate and you get a prediction for calories per minute. Add that up during the exercise, and you get total calories burned.

Sources of error

So, how well does that approach work, Well, the answer is *it depends*.

The following scenarios result in error in the prediction:

- Being dehydrated increases your heart rate because your blood volume decreases.

- Being sick or especially tired makes the prediction less good.

- Being non-average makes the prediction less good. If you have a larger or smaller heart than average, or you are more or less fit than average, the prediction will be poor.

Generally speaking, the more data your fitness device takes in, the better a prediction it can make. If there is no data entered, it will probably be pretty bad. Add age and sex, and it gets better. Add in fitness level, and it gets better still. Some fitness devices even let you enter the results of your metabolic test, which can give you decent accuracy as long as your fitness level remains the same.

How bad is the error? It’s really hard to quantify.

If, for example, you have a small heart (high heart rate) and you are very out of shape, it might overestimate your calorie burn considerably. I’m not sure what “considerably” means, but I would not be surprised to see 50% or even 100% more.

On the other hand, if you have a large heart and you are in very good shape, the device will likely underestimate your calorie burn considerably.

Calorie Inflation

Manufacturers are exercise equipment (treadmills, elipticals, etc.) tend to use pretty simple models; they often don’t even use heart rate, and if they do, their models aren’t very good. They also benefit with more sales if people are happy about their exercise, and a higher calorie burn does that, so machines tend to inflate their calorie burn numbers a fair bit – perhaps up to 30%.

I don’t know whether heart rate monitors.

Direct measurement of calorie burn

There is one way to get a great estimate of calories burnt doing exercise, at least for one specific situation.

If you have a bicycle with a power meter, the power meter measures how much force you are putting into the pedals, and therefore your bicycle computer can calculate how much work you did in kilojoules. You can then *roughly* convert that into the number of calories burned and get a decent estimate – way better than what you would get with a heart-rate measurement.