Here are my thoughts about how I think of becoming a better carver.

You should probably read my earlier posts to understand turn shape and a bit about my philosophy first:

How do I become a better skier? Stance and Turn Shape

How to become a better skier–Recommended exercises

Those posts are targeted at intermediates who want to improve their technique, and improvement there is generally fairly straightforward; fixing the stance and the path works pretty well.

Carving is an advanced skill, and that means it’s probably going to take more work on your part to get there, more time, and a fair bit of introspection about your skiing.

What is carving?

The definition of carving is pretty simple; it is skiing in a way that the skis leave two distinct tracks in the snow, like this

The skis are placed on an edge and the skis carve two parallel tracks in the snow. This happens because of the sidecut of the ski; the front and tail of the ski are wider and therefore touch first when the ski is on edge; put pressure on the middle of the ski and it bends into a curve, and that is what generates the curved path. Less angle and pressure; big radius – more angle and pressure; tighter turn. Different ski designs have different sidecuts and therefore give different turns; you can look at the radius.

Many people extol carved turns as the goal to be a “real” skier, but the reality is that carving is just one technique, one way of turning. At the opposite end of the spectrum are skidded or rotary turns, which are done with very low edge angles and twisting motions.

Both are useful techniques; as much as I like carving there are many situations where I ski blended turns (part carve, part rotary) and some situations where I ski turns that are mostly rotary (off piste, for me).

Zones of Carve and Meh

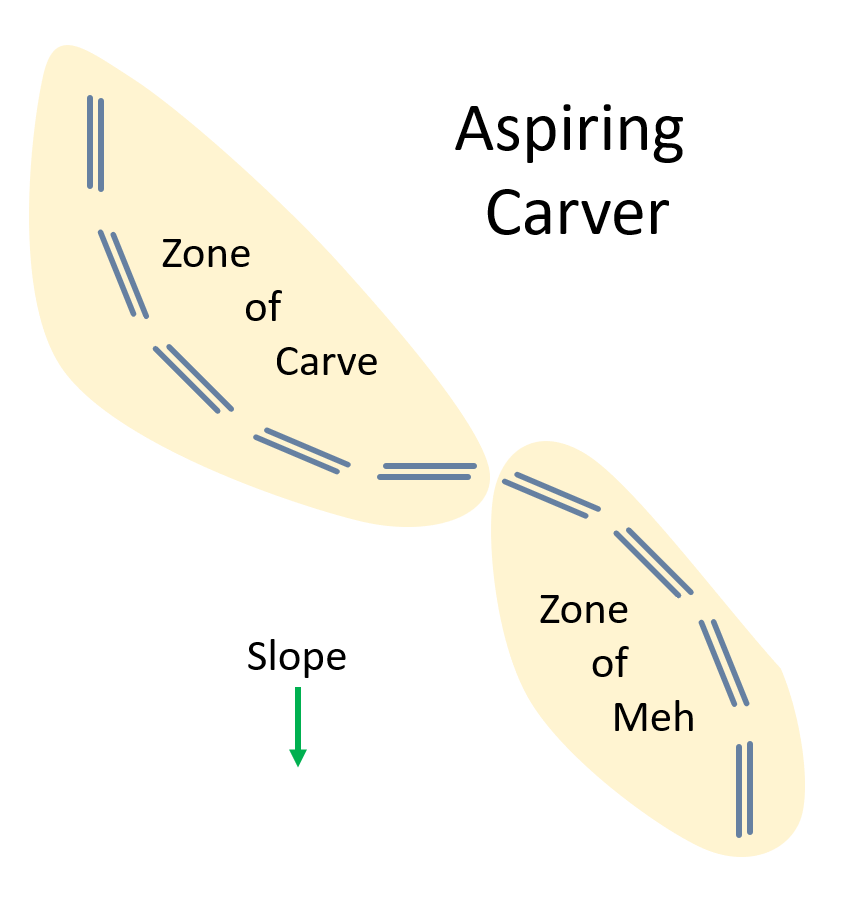

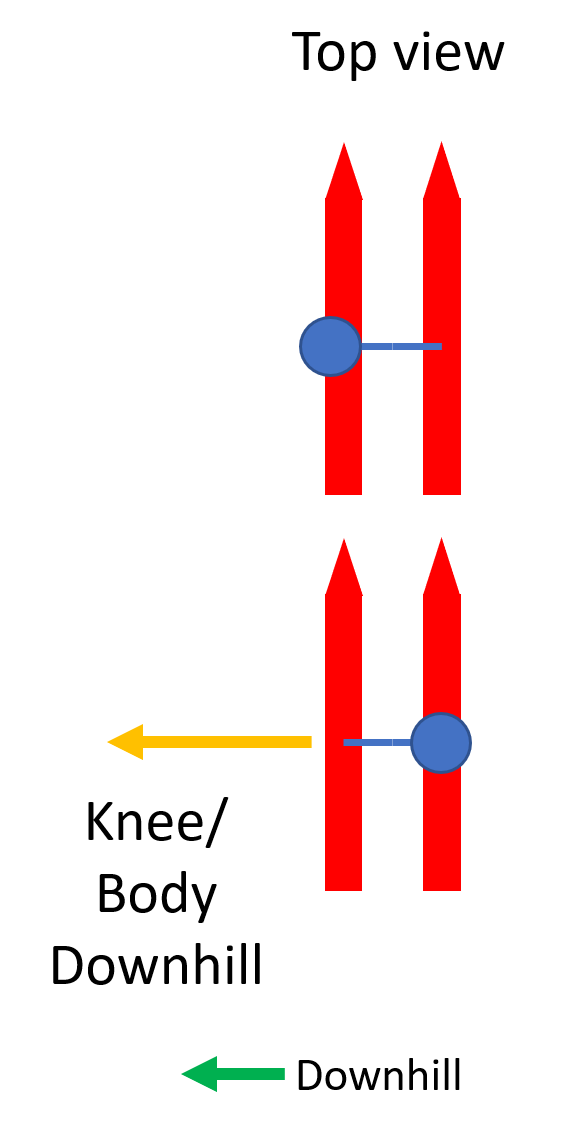

Looking the top part of this diagram, we have the zone of carve.

Look carefully at the diagram, especially at what we call “ski lead” – where the ski tips are in relation to each other in the zone of carve. The outside ski is farther back than the inside ski, and it is also more heavily weighted with the weight on biased towards the front. As the turn comes off the hill, the uphill skill is naturally in front and that knee is bent.

Getting to this point is the first step for the aspiring carver. In my examples post, the fan progression exercise is a great way to focus on this, to understand the feeling of just letting the skis run and turn at whatever rate they want to turn. Note that the fan progression is a bit antisocial as it takes a lot of width and you are skiing in a way that other people don’t expect, so make sure to look uphill and don’t do it on a crowded slope.

I also like my diagonal sideslip exercise, which allows you to play around with different stances and understand how to get the one you want.

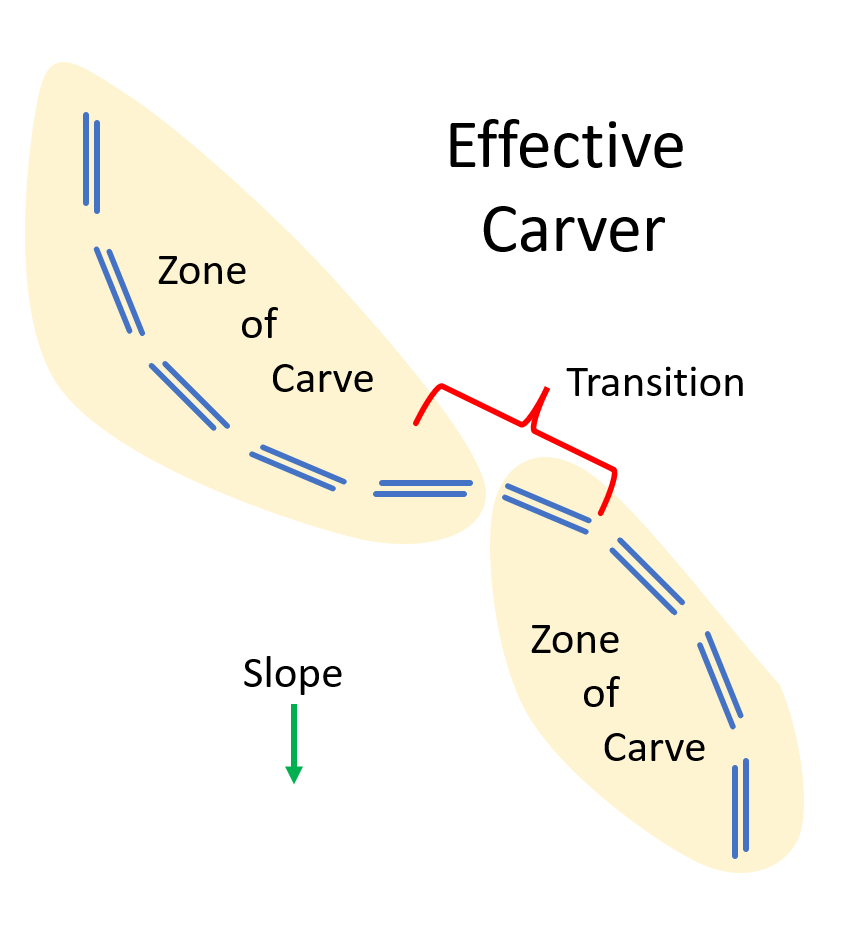

In between the zone of carve and the zone of meh, we have the transition from one turn to the other. Notice how the ski lead at the end of one turn continues into the the start (or top) of the next turn.

Why “Meh”? Well, because what we would like to see here is effective turning, but what we really see here is a lot of meh that continues until we are back at the fall line, at which point the skis and skier are in a state where they can effectively carve. Two things are common to see here; the first is that the skier is using rotary turning to get the skis turned so they are down the fall line, and it’s also common to see a transition that takes a *long* time.

It’s a little like what we see in the Z turns I talked about before, though a much less extreme version of that motion.

Why is there no carving here? It’s pretty simple; in the carve zone, I said that the outside ski was farther back and the front of it was weighted. In the meh zone, the new outside ski is out in front and that makes it impossible to have the front weighted. It also typically means that the weight hasn’t shifted to the new outside ski – the old outside ski still has most of the weight. So you just meh along until that change happens and you can get the pressure where you want.

Another way to look at this is that the zone of meh is a very long transition zone from one turn to the next.

If you ski this way, you may be unhappy with your speed control as the meh zone isn’t doing much to control your speed and you only generate decent edge angles at the end of the turn.

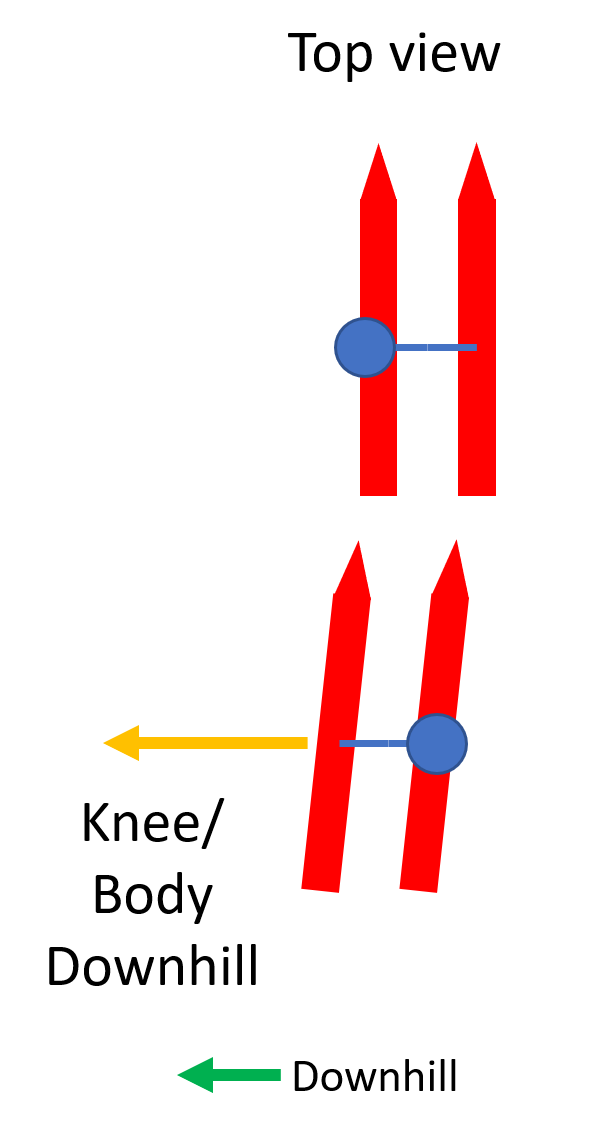

Effective Carving

The difference in this diagram is all at the transition. We go from the end of the turn where we have the old outside ski behind and more weighted to the start of the new turn where the *new* outside ski is behind and more weighted, and this happens fairly quickly. That allows us to immediately start carving on that new outside ski before the fall line and to have a higher edge angle by the time we get to the fall line. That gets out speed control that is more spread out.

The first thing required to get out of the zone of meh is to get the ski lead change done early in the transition, before you are curving down to the point down the fall line.

If you look at this PSIA medium carved turns video, you can see the ski lead change happening early in the transition. That’s what we are searching for.

Inside Ski Blocking

There’s a second issue in the meh zone that I call inside ski blocking.

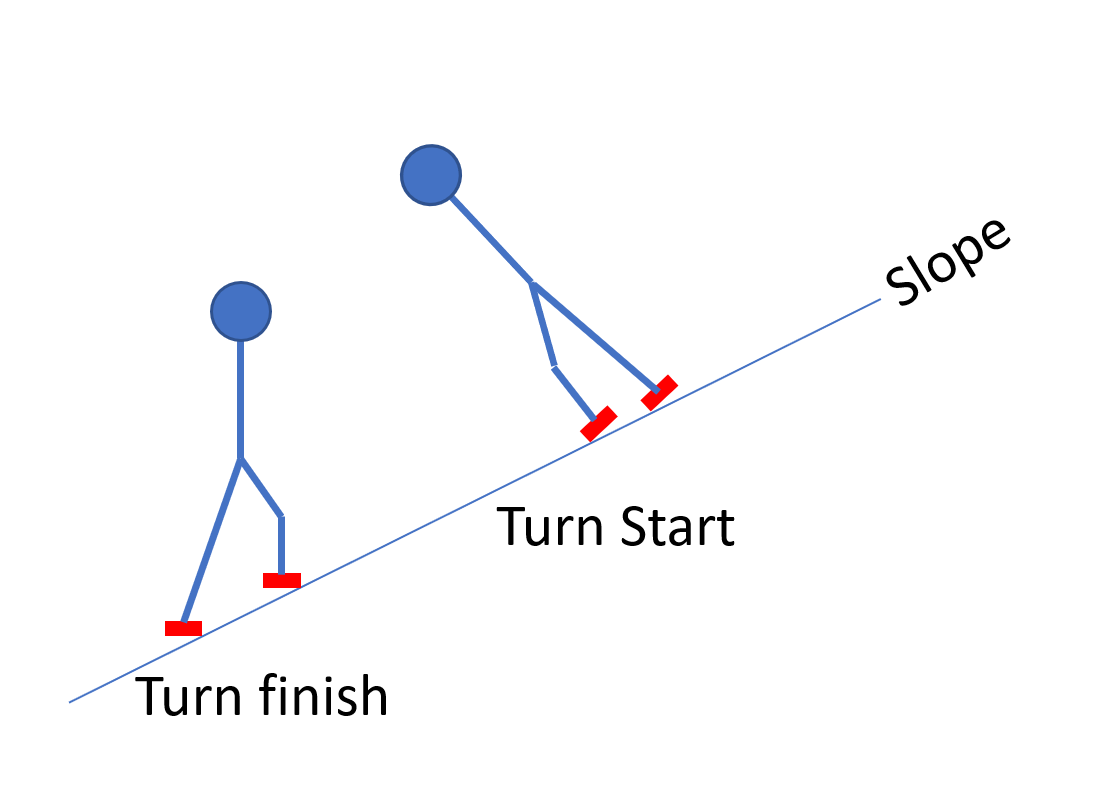

At the turn finish, we have a mostly straight downhill leg and an uphill leg that is bent because it is higher up the slope. That is a good thing – that arrangement is what gives the edging that we use to carve the bottom part of the turn.

But that’s not the position we want for the new turn; to be on our edges early – before the fall line – we will need to rotate our skis so that we are on the opposite edge. The *downhill* edge.

That is the only way to get the skis carving through that portion of the turn.

The downhill (new inside) ski presents a problem; it has a strong edge in the snow and we need to get rid of that edge and move to the new one.

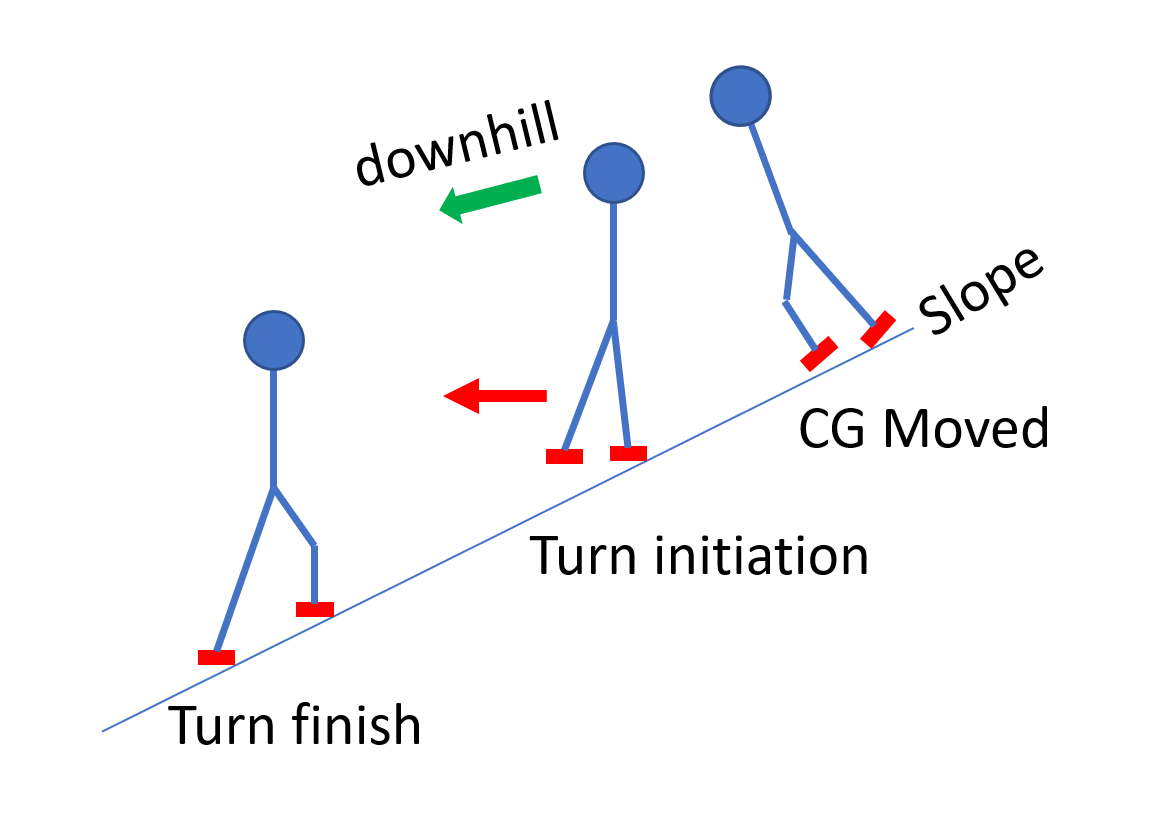

The first thing we are doing at turn initiation is straightening out the upper leg to get pressure on the ski. That reduces the pressure on the lower ski and that naturally leads to the body rotating downhill (the green arrow). However, that’s generally not enough to move the body downhill quickly enough, so we add in a movement where we actively move the downhill knee down the hill. That will pull the center of gravity downhill and put the body into the desired position.

Go back to the video and look at the turn that starts at about 1:44 in the video, focusing on the knees. Note how the downhill knee crosses over from being on the uphill side of that ski to the downhill side of that ski as part of the transition.

Oversteering

There’s one more technique to use to get on the new edges that I call oversteering (there may be a real name that I’m not aware of).

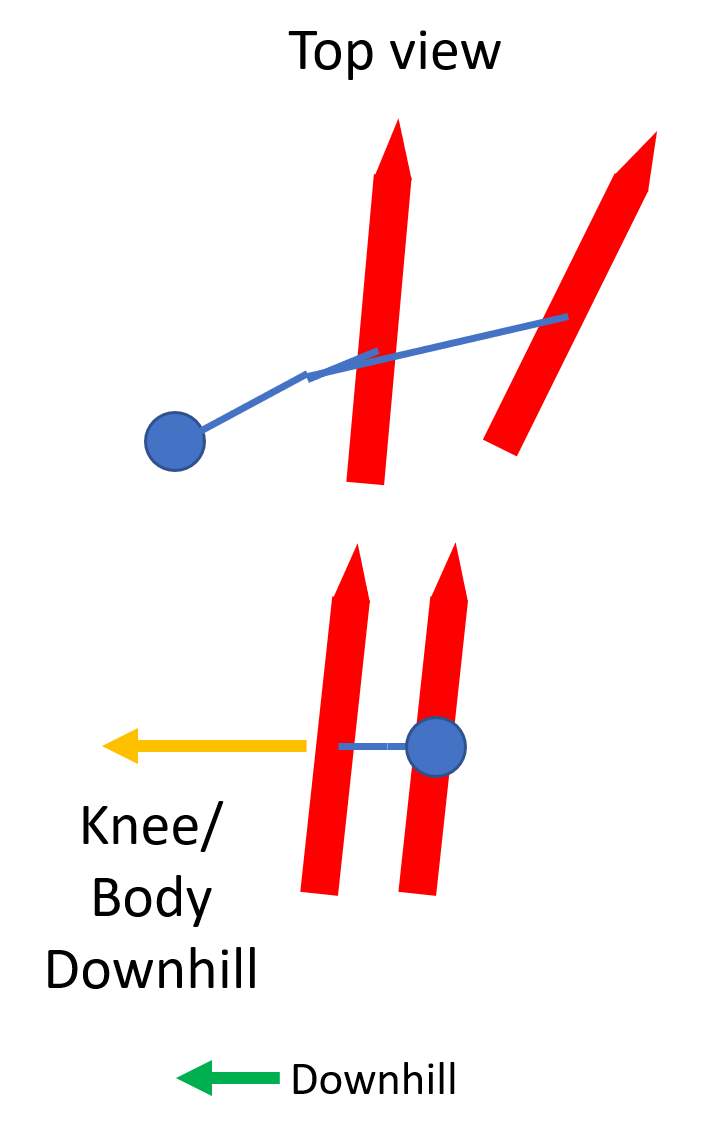

Here’s a top view of our current approach shown looking down from above.

At the end of our turn our head and body is balanced over the uphill ski so that we can have both skis on edge. Then to release that edge and get on the other edge, we shift the inside knee and therefore the whole body – including the center of gravity below the downhill ski. This works well, but that’s a fair bit of mass and it takes a little time to get that done.

Our goal is to get the center of gravity below the skis. It certainly works to move the body downhill, but we can also move the skis *uphill*. And because our skis and legs are a lot lighter than our body, this can happen faster than moving the body downhill – especially if we do both.

There is a downside. If the skis get too far up the hill or too far in front of us, we won’t be able to “catch” them on the new edges and we will simply fall over.

Turn radius

The turn radius that you choose has a big effect on technique. If you are doing big long-radius turns, you can do them without a whole lot of movement; you don’t need big changes in ski lead and therefore you probably don’t need knee initiation. You can do most of it just with ankles.

Medium radius is going to require more activity on both ski lead and the knees to get the transition to happen quickly enough.

Short radius turns use pretty much the same technique as medium radius ones but can definitely benefit from a little bit of oversteer (or overedge) as that will really pop the skis across into the new turn. When you fall down, you’ll know that you went too far.

Exercises

I really like the one-ski lift the tail exercise I describe in the other write-up. Get into a traverse, lift the tail of the new inside ski 3” off the snow, and then just let your body move downhill and into the turn. The reason this one works so well is that to get the tail of the inside ski up you must have weight on front of the new outside ski or it doesn’t work. Do this on an intermediate slope where you are comfortable; it is going to take time to get used to a turn initiation that is much less active than the one you are used to.

If you have trouble with the position, go back and do the forward sideslip exercise. One more thing to check is your ski spacing; if you ski with your skis very close together you can’t get the angles you want because your knees will bump into each other. Note the ski spacing of the yellow skier in the video.

Focus on what I would call “big swoopy turns”; you should be nearly across the fall line at the end of each turn. This is sometimes called “skiing the slow line fast”; you are taking a path that is much longer and therefore looks slower but because you are carving you are carrying a lot of speed.

So, what do you think ?